Harry, an ambitious and idealistic inventor with a slick line of patter always ready to hand, roams this in-between terrain, peddling assorted inventions. Way out West, as Harry Ransom, the narrator of "The Rise of Ransom City," explains it, are "territories where the future was still open, where laws were still unsettled - I mean not least what they call the laws of nature, which as everyone knows are different on the Rim." Nevertheless, it's instantly recognizable as a version of the Wild West, a frontier land with towns named Clementine, Gibson or Jasper City, sandwiched between the distant, civilized East and, to the West, a region known only as the Rim. The setting is not, of course, called America (any more than Middle-earth is called England).

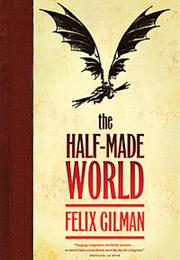

American writers ranging from Stephen King to Michael Chabon have tried to fill this archetype gap, but it isn't always easy to create imagery and ideas that resonate, which is one reason why so much fantasy falls back on Anglo-Saxon and Celtic motifs.įelix Gilman's two vaguely steampunkish novels, "The Half-Made World" and the just-published "The Rise of Ransom City," come closer than many previous efforts to nailing America's conflicted collective unconscious. In place of ancient folklore handed down from generation to generation, we have a shallow, polyglot history imposed over a native culture that was demonized and in many cases eradicated by European settlers.

Compared to British fantasists, American writers have often felt the lack of a deeply rooted national mythos.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)